Well, friends, the world sure looks different than it did when I last posted. These next two things (Thing 13 is video and Thing 14 is audio) are now incredibly topical as everyone who works in a university adjusts to teaching and learning online. For thing thirteen, we are asked to choose one of three video sharing sites:

- Youtube

- Vimeo

- Media Hopper Create (a media service for the University of Edinburgh)

After experimenting with some of the features of the site such as creating a playlist, we’re asked to connect this to some of the other 23 Things, answering questions such as:

- what accessibility options are available?

- do I find the platform usable?

- how findable is the licensing information?

Reflections on what I learned and how my thinking changed follow.

Why Youtube

I chose to explore Youtube for this post as it’s the video platform out of the three I am most familiar with, and I thought it would be interesting to dive deeper into it. When do I use Youtube? On days where there is a lot of book ordering to do, to turn this into an enjoyable task, I let myself a have a little treat: I listen to classical music. However, I don’t actually engage with Youtube very much when I do that–a very quick search for the music I want to listen to, several checks that my headphones are securely plugged in and not leaking sound, and then the platform itself fades into the background.

Playing with features

I’d forgotten that Youtube has been a subsidiary of the almighty Google since 2006–the reminder came when I was asked to log in and supply my gmail account name and password. It turns out that I had previously followed two channels, SciShow and VlogBrothers, though it has been over six years since I watched a video on either. I’m including the link to the former in case anyone reading is looking for educational and entertaining videos during lockdown! (Hat tip here also to the Smithsonian’s Distance Learning Resources.)

YouTube channel is a user’s home page and public-facing account on Youtube. It’s possible to follow (subscribe, in the language of Youtube) any channel without creating one of your own. When you’re logged in it’s possible to add videos to your list of items to watch now (queue), or add them to a list to watch later. And yes, I’m freely admitting that I wasn’t aware of that either of things before writing this post; even when I did use YouTube more actively I was a very passive user of it.

And of course, even I knew that one need not even have an account to watch a YouTube video.

However, you do need to create a channel if you want to make playlists, comment on videos, or upload your videos of your own. I created a quick playlist of versions of versions of Benjamin Britten’s Turn of the Screw, and found it quite easy. Some of the Youtube channels I follow are specifically focused on educational content, and I can easily imagine the creation of playlists for teaching and learning, or even as a learning activity (create a playlist of four videos on topic x and write a reflective piece assessing these choices could be an interesting assessment). YouTube channels seem to be a thing within higher education as well; in writing this post, I discovered my university library’s own YouTube channel. It’s interesting to think how I might incorporate this into my approach to supporting students–for instance, perhaps by emailing a link to a relevant video in addition to or instead of typing out instructions…

Other Things

Applying things I’ve learned in writing other posts, I’ll now to turn considering YouTube’s accessibility and usability, as well as how easy it is to find licensing information.

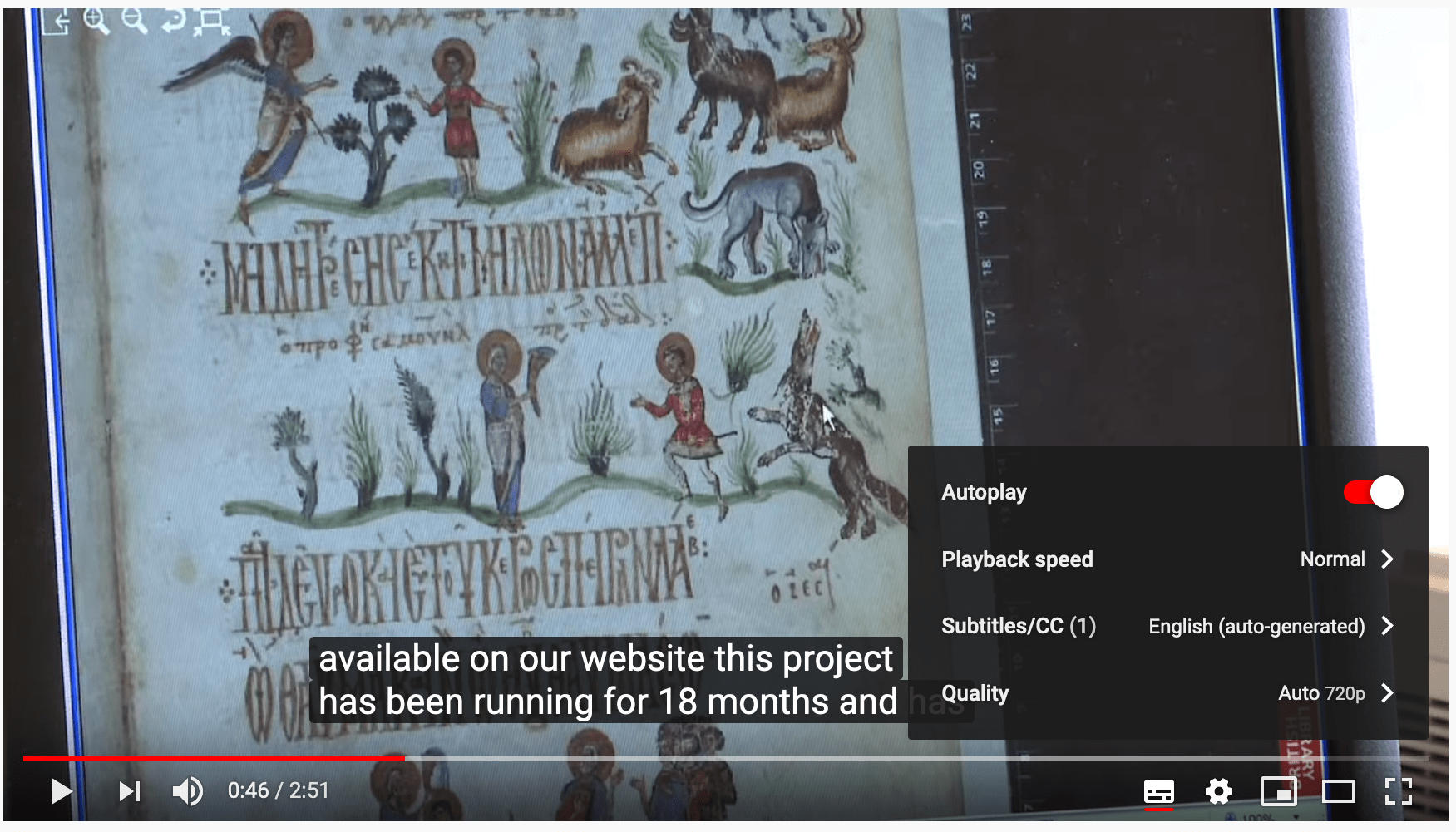

In terms of accessibility, most of my library’s Youtube videos are made via Adobe Sparks, so they include background music, text, and images, but no speech. There is an option to adjust playback speed via the settings wheel at the bottom of the video. Taking a quick look at a video made by the British Library, I can see an option add auto-generated subtitles, including auto-translated subtitles (potential source of lockdown amusement?), and the opportunity to adjust the playback speed.

On thinking about it I can also see where the option to adjust the video quality is an accessibility feature too, enabling viewers with slower internet connections to still watch a video (YouTube, according to its help page on video quality, adjusts the quality of the video stream based on the conditions under which a user is viewing.)

As far as useability goes, there is a reason YouTube is cited as one of the world’s most popular search engines, and one of the internet’s most popular websites (the Wikipedia article on the social impact of YouTube that was part of the recommended reading for this Thing strongly underscores both of these points). Billions of people find it very useable indeed.

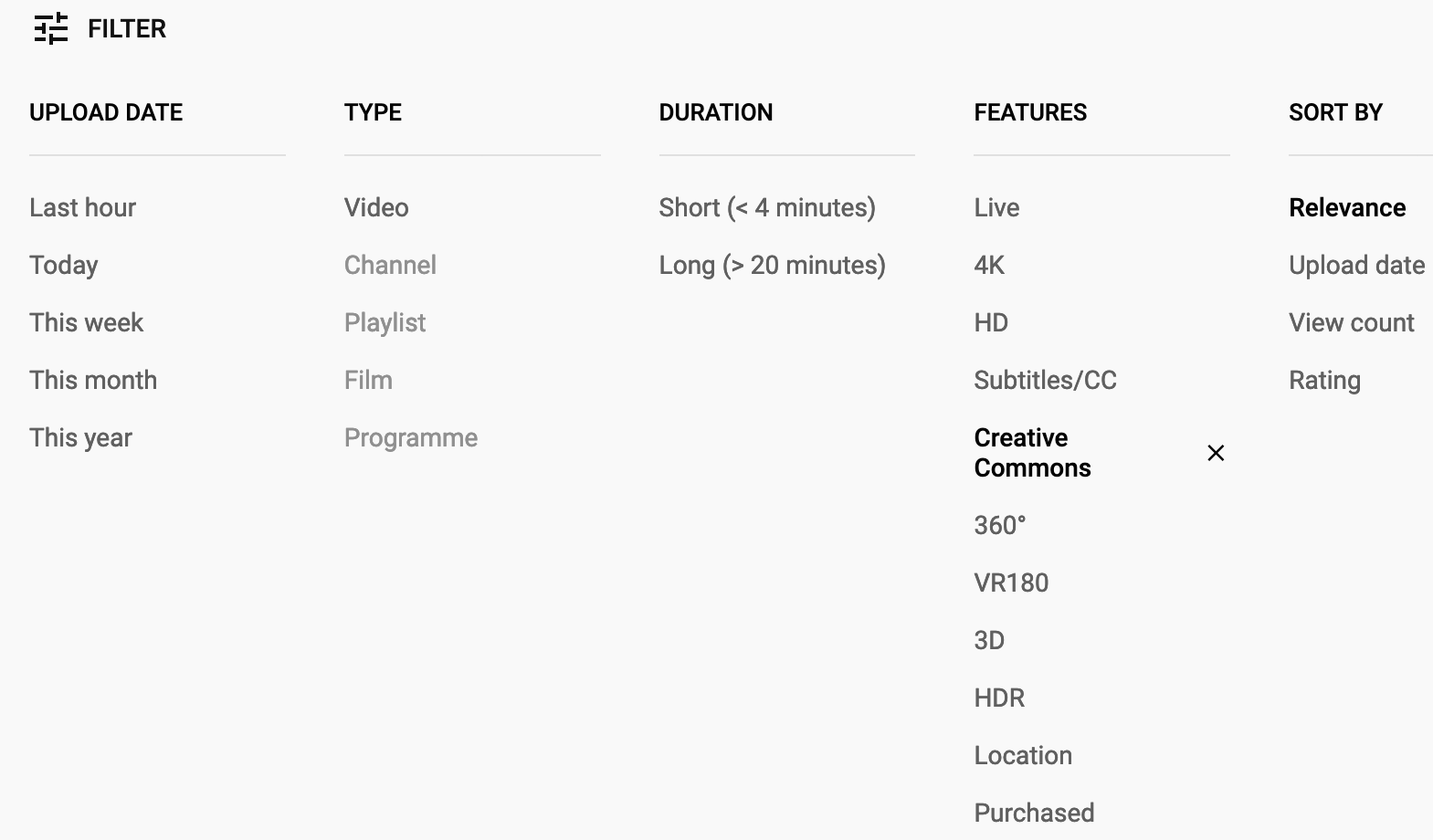

Trying to find licensing information for the video I screencapped above, was surprisingly difficult. The text below the video contained no information on licensing, nor did their seem to be any option check this on the menus available within the video itself. Checking ‘home’ and ‘about’ pages for the British Library’s channel yielded no information. After doing some Googling about it, I discovered that if a video has licensing information, it should appear underneath the ‘Category’ in the video’s about section; to limit a search to creative commons content, you can filter the search like so:

Doing a search for British Library and filtering to creative commons shows a number of videos on their channel are licensed. Youtube’s own copyright page focuses on the copyright situation in the United States, but offers a good explanation of ‘fair use’ and its own stance towards creators’ fair use freedoms and takedown requests. The TL;DR is as you might expect: no license = no freedom to reuse without permission from the rightsholder.

Concluding Thoughts

Before the past fortnight, I would have had no thoughts about the use of online video in education. I had never used or created it in my own teaching, and my encounters with it had largely been to discourage it. Professor Paul Freedman’s video lectures on the early Middle Ages have likely made him one of the most recognisable historians of the field, but I have advised students to cite his publications, not his videos, as appropriate academic resources. I’ll get into why I stand by this in a moment, but first I want to talk about how my perspective on video has changed.

The coronavirus pandemic has created a huge, rapid shift in the way we teach and learn. This past week has seen my first experiences as a creator of web video, as I’ve worked on making a video series, ‘Your Remote Library’, using Panopto, to introduce our online library to students who might be anxious about lack of access to print materials for the foreseeable future. On Wednesday, I delivered my first-ever online lecture, which I created as a series of four videos, linked together by a playlist (which had some hiccups, I have confess)…before writing this blog post, it would never have occurred to me that I could (this is going to make me sound like I just discovered that the internet exists)…learn to do it by, you know, watching someone else do it, rather than frantic googling to enable the skimming of Panopto’s help pages, and consulting my notes on the ‘how to use Panopto’ lecture I attended via Blackboard Collaborate just a week ago.

One of the recommended pieces of media recommended for further exploration on the topic of video is Chris Anderson’s TED talk, ‘How web video is powering global innovation‘. I was blown away by the idea of scientific research being shared by video–it makes such sense, when someone needs to replicate a sequence of steps and an experimental setup, to show it to them by video, rather than with pictures and descriptive text. In our current circumstances, news stories such as this one have medical professionals are sharing information about the coronavirus treatments via social media, including video sharing sites, alongside traditional processes of publishing research.

From my own experience working in higher education, there seems to be a perpetual distrust of video sharing sites, and particular of video recordings. Videos of lectures and seminars, are seen as a way for the university to either monetize lecturers’ intellectual property (or at the very least, potentially put it beyond their control), or pave the way to reducing staff numbers. Furthermore, video as is ranked far below the written word as a reliable academic source. Students in some of the disciplines I support might be discouraged from citing web video as an information source for some types of writing, such as an essay; and encouraged to cite it in others, such as a reflective piece on the work of a particular performance artist. The democratic and open elements of web video–what Chris Anderson celebrates as the power of the crowd–represents a different set of values than systems which train students to participate in discourses of experts talking to other experts.

Expertise matters, and developing and recognising its value seems to me to be one of the things higher education is fundamentally about. We guide students towards an understanding of different types of information in our teaching as librarians; we put critical thinking on most assessment rubrics as lecture, and overall what comes out of this, hopefully, is that someone who has been through a university education has developed habits of thinking, habits of assessing and using information, that they will use for the rest of their work and lives.

Context matters too. The reason I discouraged students from using Freedman’s videos not just out of distrust of educational video, it’s because the videos record his lectures, not his academic research. Ideally when someone is producing a piece of formal academic writing, they are engaging directly with a scholar’s latest arguments and interpretations; lectures typically provide the framework and background knowledge that enables students to do that. It will be interesting to see how the current situation changes things–whether scholars start to disseminate their work, not just their teaching, on video, and how this might change teaching and learning in the future. I suspect Thing Thirteen is going to continue to be relevant in ways I haven’t even thought of yet.