Excited to say I am past the halfway point for completing my 23 Things for Digital Knowledge posts! It has been an educational journey and this week I am exploring the world of open educational resources, or OERs.

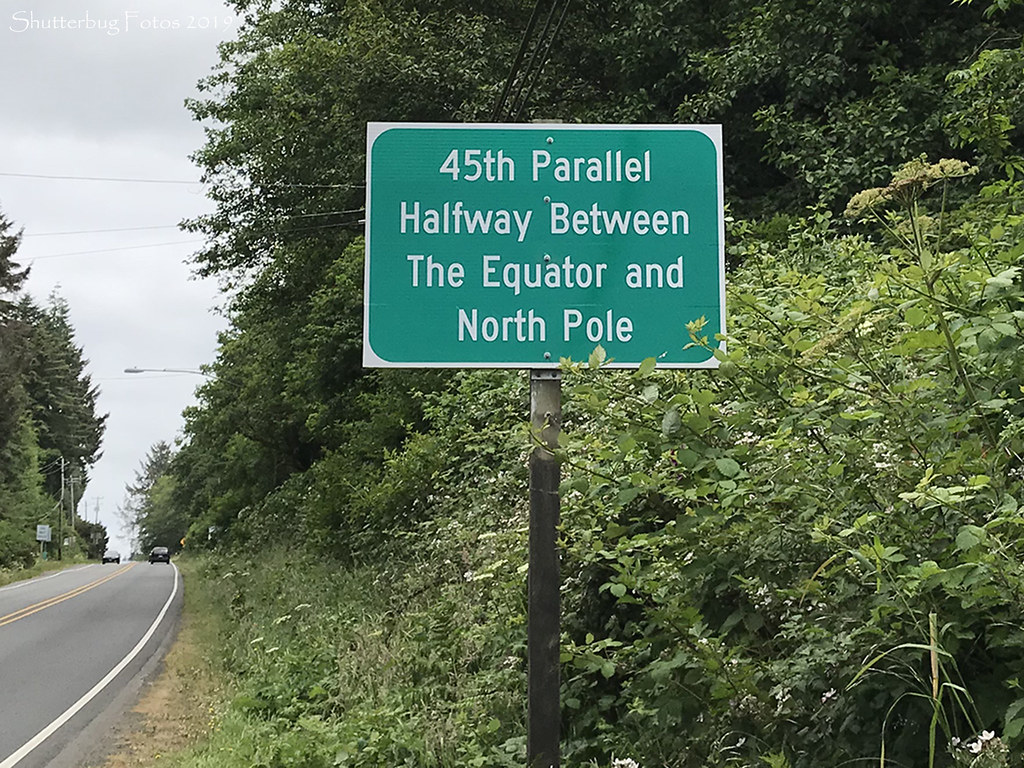

“45th Parallel” by Shutterbug Fotos is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

“45th Parallel” by Shutterbug Fotos is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

In this post I will discuss the definition of an OER as I understand it, things that surprise me about it, and will conclude by reviewing an OER in my field, medieval studies.

What’s An OER?

These are materials for teaching and learning which are made available online with a license that encourages adaption or reuse. The Open Education Handbook offers an excellent overview, which stresses the wide range of forms OERs can take: course materials, learning objects, tests, games, and ‘any other tool, material, or technique that supports access to knowledge’. As an academic subject librarian I have become increasingly aware of OERs through my work with dissertation students in the history programme: a lot of students are looking for primary sources to fit very specific research questions, and I have increasingly been suggesting material available on the open web as suitable for their work.

Surprise!

I had not thought about this before writing this post but it is one of the key things I have taken from this exercise:

Open Access ≠ Open Educational Resource

One of the things the previous post on copyright taught me is that there are different levels of open licensing. For instance, because an image is open available online doesn’t mean that it can be freely re-used, remixed, adapted, or shared. By licensing their content, creators can express their preferences of what they want to happen to their creation in the future. Material from the digital archives I frequently support students in finding and using might be open access but not fully open in other ways.

Take the digitised collections of the John F Kennedy presidential library, which a student and I recently explored as part of a research consultation. A selection of the WWII letters of Joseph P. Kennedy Jr, have been digitised, and come with a extensive copyright note. Here’s an excerpt:

Documents in this collection that were prepared by officials of the United States as part of their official duties are in the public domain.

Some of the archival materials in this collection may be subject to copyright or other intellectual property restrictions. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish.

In other words, the material is open access, but there are potential restrictions around reusing and adapting it.

The openness of materials on museum and archive sites can vary. In teaching classics and medieval studies, I frequently find myself using the wonderful online collections of the British Museum. Most of their online images are licensed under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Sharealike 4.0 License (CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0), so the material can be reused and adapted as long as the image is shared under the same license, it is attributed to the British Museum, and is not used for commercial purposes.

Clearly, this is more open that the digitised letters from the John F. Kennedy presidential library, but according to a definition put forward by Jordan Hatcher of the Open Data Commons, it would still not qualify as an open educational resource. (See also the Open Definition, to which Hatcher links).Why? Because the restriction on commercial use means that their instances where the British Museum’s images of items in the collection cannot be freely used, reused, adapted, and shared.

Within these definitions, there seems to me to be an implicit statement of values:

- maximum openness is best

- restrictions are a problem

I can see the clear positives in this: maximum openness promotes the democratisation of knowledge and learning, ensuring that no one government, professional organisation, or educational body has the right to say what someone could or should learn. But this attitude also makes me think a bit: is maximum openness always best? What happens when someone remixes, reuses, or adapts your open educational content to teach a lesson with which you disagree?

This is something I have only just started thinking about because of these posts, and would welcome thoughts and suggestions for further reading.

A Medieval Studies OER: Epistolae

Epistolae is one of my very favourite medieval studies resources. It’s a collection of Latin letters written by and to women between the fourth and the thirteenth centuries, and includes the original language and English translation. The Latin texts of the letter are out of copyright, meaning that they can be freely used, adapted, and shared. According to the about page, the project is designed to be collaborative, so the translations are presumably free to be shared, used, and adapted as well, though I can’t find specific copyright information on the site.

The collection doesn’t include letters written in languages other than Latin, and it includes primary noble or royal women, but even with these caveats, it is a resource I love to promote for teaching and learning. The collection of texts is larger than any source book on medieval women I know of, and the letters are given in full, which lets students and teachers grapple with the lessons of an entire text (sourcebooks frequently offer only short snippets). The interface is clear, simple, and easy to use: it can be searched by the names of female letter-writers and recipients, or within the letters themselves, for keywords such as ‘donation‘. A biography of each woman, and bibliography about her makes it a valuable tool for further research.

Concluding Thoughts

This pair of tasks has been my favourite part of 23 Things so far: it has taken topics I knew very little about, helped me to learn more about them, and sparked my desire to keep learning.